In warrior (virabhadrasana) two, you may have heard the cue to square your hips toward the side of the mat, but is that necessary? Is it a good idea? Is it even possible? In this post, I’ll look at the anatomy of the hips to answer those questions.

Joint positions

Let’s start with the positions of the joints. In warrior two the hips are abducted, which means that the thighs are opened out to the side, away from the midline of the body. The front hip is also externally rotated, i.e., the front of the thigh is rotated away from the midline along the long axis of the thigh, and the front hip is flexed.

To see whether the hips’ range of motion in those positions will allow the pelvis to be square, we first need to understand what limits the movement of joints.

Joint constraints

There are four major constraints to joint movement. The first is bony compression—basically, the bones bump together and they can’t move any further.

The second constraint is ligamentous. Ligaments are tough fibrous connective tissues that hold bones together. As a joint nears its end range, the ligaments become taut, resisting further movement.

The third constraint is muscular. Muscles can contract actively to resist joint movement, but muscles can also generate passive tension, which is simply resistance to being stretched. Whether muscle tension is created actively or passively, it can limit the movement of joints.

Finally, there’s soft tissue compression. For example, if you fold forward in a forward bend and your abdomen presses against your thighs, that’s will block further movement.

The last constraint doesn’t play much of a role in warrior two, but any of the first three could limit hip range of motion in the pose.

Bony constraints

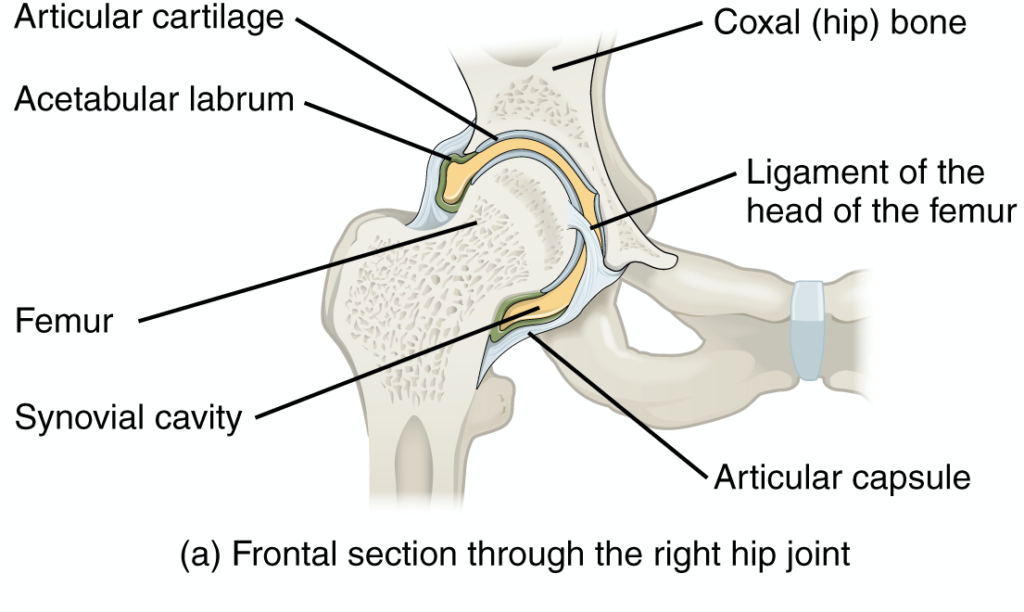

At the top of the thigh bone, or femur, a round head fits into a hollow socket on the pelvis called the acetabulum. The neck of the femur connects the head to the shaft. As you abduct and externally rotate your front hip in warrior two, the neck of the femur could contact the back rim of the acetabulum. If that happens, it will limit further movement. If you try to abduct your thigh more, the pelvis will be pulled along for the ride, bringing the back side of the pelvis forward—in other words, rotating the pelvis toward the front thigh.

Ligamentous constraints

There are three major ligaments that stabilize the hip joint.

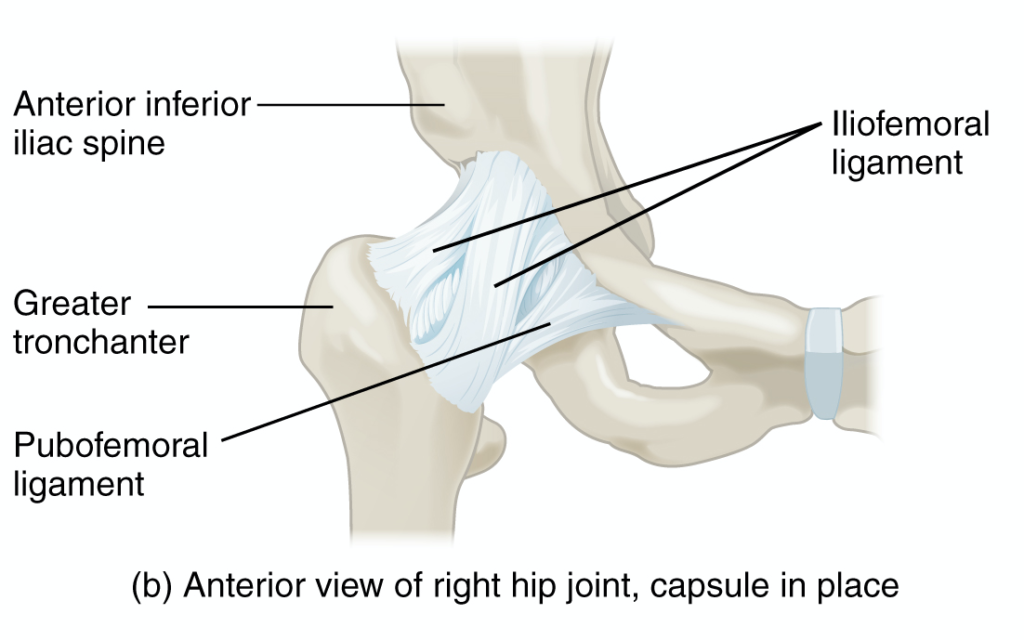

One of them, called the pubofemoral ligament, runs from the pubis, or the front of the pelvis, to the intertrochantric line just beyond the neck of the femur. Its primary job is to limit hip abduction, although it can also play a role in limiting external rotation.

The iliofemoral ligament, the strongest of the three ligaments, is sometimes called the “Y” ligament because it forms an upside down Y-shape. It runs from the ilium, or the upper part of the pelvis, to the same intertrochanteric line of the femur. Its job is to prevent hip external rotation.

As you move the front hip into abduction and external rotation to come into warrior two, both of those ligaments may be pulled taut, limiting the range of motion and rotating the pelvis toward the front thigh, just like what might happen with bony compression.

The third hip ligament, called the ischiofemoral ligament, connects the back of the pelvis, or ischium, to the femur. It’s not likely to limit the movement of the front hip. But all three hip ligaments will be pulled taut during hip extension, and that could play a role in what happens in the back hip.

Muscular constraints

The muscles that resist hip abduction are the hip adductors. They’re a group of five muscles that lie on the inner thigh. They have various attachments to the pelvis from the pubis to the ischium. Most of them attach to the back of the femur along a line called the linea aspera. Their job is to adduct the hip, pulling the femur toward the midline, meaning they resist hip abduction. As the front hip moves into abduction in warrior two, the adductors have to lengthen. If they contract, of course that would resist the movement. But even if you don’t actively contract the adductors, they will generate passive tension as they stretch, which can have the same effect.

The front hip and pelvis

As you come into the warrior two, those constraints, whether they are bony, ligamentous or muscular, will limit the amount of hip abduction and external rotation available in your front hip. When you hit the limit of range of motion, which might be due to different constraints for different people, one of two things will happen.

If you keep your front thigh pointing in the same direction as your foot and your knee on top of your ankle, your pelvis will rotate, at least a little, in the direction of your front thigh. Although it may still face the side of the mat, more or less, it won’t be square.

What happens if you try to square your pelvis? Those same constraints will cause the front the thigh to veer inwardly, pulling the knee in as well (or the pelvis out to the side).

In other words, the front thigh and the pelvis act like a see-saw. Either the knee falls in or the pelvis rotates toward the thigh.

The back hip

What happens in the back hip will also affect the front hip.

For instance, if you take a very narrow stance, crossing your back foot behind your front foot, your back hip will be in relative hip extension, i.e., your thigh will be behind your pelvis. If you recall, all three major hip ligaments pull taut in hip extension. As they reach their limit of extensibility, they will pull the back side of the pelvis backward, which will have the effect of moving the pelvis toward square—and, more than likely, causing the front knee to veer inwardly. Taking a wider stance will allow the back side of the pelvis to rotate forward and allow the front knee to re-center itself on top of the ankle.

What’s the takeaway?

To summarize, the constraints to hip range of motion ensure that in warrior two you almost certainly cannot abduct your thighs 180 degrees apart from each other. If you keep your front knee on top of your ankle, so that the thigh points, more or less, in the same direction as your toes, the back side of your pelvis will be pulled forward.

Is that ok? I think it’s better than the alternative. Squaring your pelvis toward the side of the mat will likely pull your front knee inwardly, creating an uneven distribution of forces through the knee. Although yoga teachers sometimes exaggerate the risk of that, which I don’t think is necessary—the knee is a robust and resilient joint—in the long term, if you keep your knee centered over your ankle and don’t allow it to veer inwardly, you’ll have a more even distribution of force through the joint and a better weight bearing architecture.

So, my preference in warrior two is to keep the front knee on top of the ankle and to let that thigh dictate the position of the pelvis. If your pelvis isn’t square, that’s fine. You can still turn your chest toward the side of the mat because your spine can rotate.

Final thoughts

But beyond the narrow question of warrior two, I think it’s important to continue to question rigid rules about alignment. If we can let go of focusing on the “right” way to do a pose, the asanas can become a vehicle for exploration.

So, when you find the position of the feet and hips that works for you, that allows you to feel stable, comfortable and strong and that allows for good force transfer through the joints of your body, that’s the right warrior two for you.

To me, that’s a far more interesting and informative way to practice yoga than trying to force your body to adhere to rigid rules about alignment.