How does stretching make you more flexible?

Intuitively, it seems that it must have something to do with your muscles—that they must lengthen or that the tissue must become more pliable over time. Yet, as we’ve seen, the evidence doesn’t bear that out.

Stretching makes muscle tissue more pliable in the short term, but those changes don’t last. Muscles revert to their normal stiffness within minutes after a stretch. And it’s pretty unlikely that stretching will make your muscles physically longer unless you’ve been previously injured or immobilized. The resting length of a muscle is determined by the distance between its attachment points on your bones. Longer than that, and it wouldn’t be functional.

Yet, clearly, you can become more flexible with time. So how does that happen? The answer lies in your central nervous system.

Stretch receptors

Your nervous system controls your muscles. Without input from the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord), a muscle is just a piece of meat. It can’t do anything on its own.

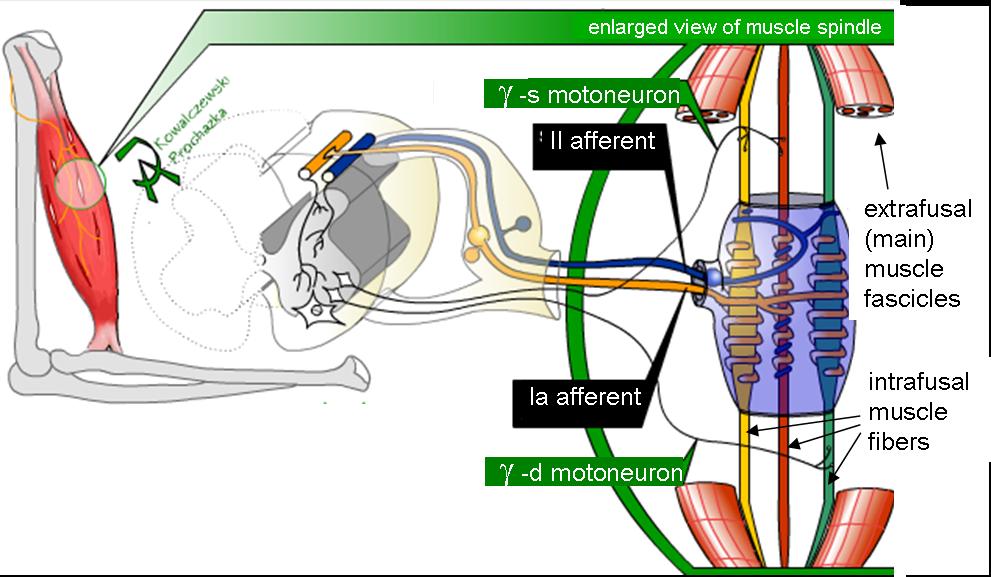

The central nervous system continuously monitors the length of your muscles through sensors called muscle spindles. When a muscle spindle detects a change in muscle length, it signals the spinal cord. That signal initiates what’s called the stretch or myotatic reflex, which causes the muscle to contract to resist the stretch. That’s partly why you may feel that your hamstrings’ first impulse when you move into a forward bend, such as paschimottanasana, is to fight back.

The stretch reflex reacts most strongly to sudden changes in muscle length. This is the principle behind the test in which your doctor taps the quadriceps tendon at the front of your knee. The hammer strike stretches the tendon quickly, triggering a reflex contraction of your quads that extends your knee.

If a stretch is sustained, the muscle spindles adapt. Their rate of firing slows down, reducing the input to the spinal cord and shutting off the stretch reflex. However, this is a also short-term adaptation and can’t account for long-term changes in flexibility.

That’s because your brain continuously adjusts the sensitivity of your muscle spindles to provide information about the state of your muscles no matter their length. The system needs to be responsive and dynamic. If you move to a new position or even deeper into the stretch, the spindles will be ready to fire again.

The brain

Input from stretch receptors doesn’t just travel to the spinal cord (where the stretch reflex occurs). It also flows to the brain. This is important, because as I mentioned, your brain needs updates about the position of your body at all times. Information from muscle spindles is integrated with signals from sensors in your tendons and joints (as well as input from your eyes and vestibular system) to form a complete, and constantly changing, picture of where you are in space.

This is vital information for your brain. Without it, you wouldn’t be able to maintain your balance or to react to external threats. It’s also important for maintaining the integrity of your joints and preventing injury. In fact, it’s so vital that your brain is likely to interpret a muscle length outside of its normal experience as threatening in and of itself.

Pain is your brain’s reaction to a perceived bodily threat. It’s the brain’s way of getting you to change your behavior. If you force your muscles to lengthen beyond their accustomed range, you’ll feel pain and you’ll back off the stretch. That range of movement may or may not actually be injurious, but your brain will play it safe and ask questions later.

Current research suggests that the way stretching works is that it increases your brain’s tolerance for the sensation of stretching. In other words, you eventually get used to it. Your brain no longer sees the sensation as threatening or painful, and it incorporates that range of movement into what it perceives as safe.

On the other hand, if your brain continues to perceive a particular range as unsafe, it doesn’t matter how much stretching you do. Your long-term flexibility won’t increase, which is why some people can stretch their hamstrings for years and never touch their toes.

This brings up the question of whether stretching is even the most effective way to increase your flexibility. I think not.

If flexibility comes from your brain, the key to increasing your range of motion is to reprogram your brain, not to pull on your muscles. In fact, if you perceive a stretch as painful, it’s probably counter-productive. Your brain may eventually get used to it, but you’ll probably make faster progress if you reassure your brain that it’s safe in the first place.

That’s the principle behind the Feldenkrais method—exploring movement options within a safe, easy range, which often results in being able to move much farther than you thought you could without any sensation of discomfort or stretching.

It’s also a fundamental principle in yoga, although we often forget it. It’s easy to get caught up in the excitement of trying to keep up with your bendy neighbor on the mat next to you. But ultimately, yoga is about getting to know your mind better, not about contorting your body into the deepest stretch possible.

What does all this mean in practice?

Here are a few principles to keep in mind:

- Warm up your muscles before moving into a stretch. Warm muscles are more viscous and pliable. They’ll stretch more easily and will be less likely to trigger a reflexive contraction of the muscle. And your brain will be less likely to perceive the sensation as painful.

- Focus on small, easy movements within a pain free range, especially during your warm up. This is sometimes referred to as dynamic stretching, which has been shown to increase flexibility as much as static stretching.

- Remember, flexibility comes from your brain. Don’t push yourself to the point where you’re feeling pain. Aim to keep a calm, relaxed state of mind throughout your practice.

Other posts in this series:

What happens when you stretch a muscle? (Part 1)

What happens when you stretch a muscle? (Part 2)

References:

Photos and Illustrations:

“Muscle spindle model” by Neuromechanics – Own work. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This post is really informative for us! Thanks for sharing. We also work in the same field.To know about the benefits of stretch healing, visit us at http://bit.ly/1vgQLxZ

[…] 日本語訳 Yo Miyamura 原文リンク How does stretching make you more flexible? Joe Miller […]